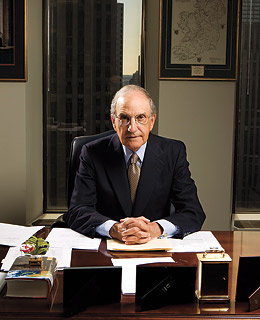

George Mitchell's father was an orphan, his mother a Lebanese immigrant. They were insistent that even in America, there were no shortcuts to success. Their son served in the Army, worked his way through night school to study law and went on to serve most of his career in government, including 14 years as a U.S. Senator from Maine (he was also Senate majority leader, the second most powerful elected office in the land).

When Mitchell chose to leave the Senate in 1995, he was just 61 and had earned a reputation for unflappability. President Bill Clinton named him special envoy to Northern Ireland, where he was tasked with taming the sectarian violence that had claimed more than 3,000 lives. In 1998, after three long years of squabbles that made the partisan headaches of the Senate seem quaint, Mitchell presided over 36 hours of negotiations that produced the historic Good Friday Agreement.

Mitchell succeeded in his shuttle diplomacy because he managed to build trust among the parties. And when he was invited by the commissioner of Major League Baseball to head up an investigation of steroid use in the league, he was asked to restore trust in baseball. In the previous decade, Mitchell, who played a lousy second base as a boy, had seen home-run totals soar and cap sizes swell while nearly everyone involved in the sport—the players' union, owners, commissioners, the media and fans—turned a blind eye to the "troubles" ailing the American pastime.

Mitchell would inevitably make enemies when his findings, released in December 2007, implicated not only designated villains like Barry Bonds but also national icons. But whenever he talked about why he took the job, Mitchell mentioned the "real victims"—the honest players who had rejected illegal shortcuts. It is left to baseball to clean up its act. But by making officially known what was long knowable, Mitchell has added yet another chapter to his distinctly American story.

Power is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and a columnist for TIME